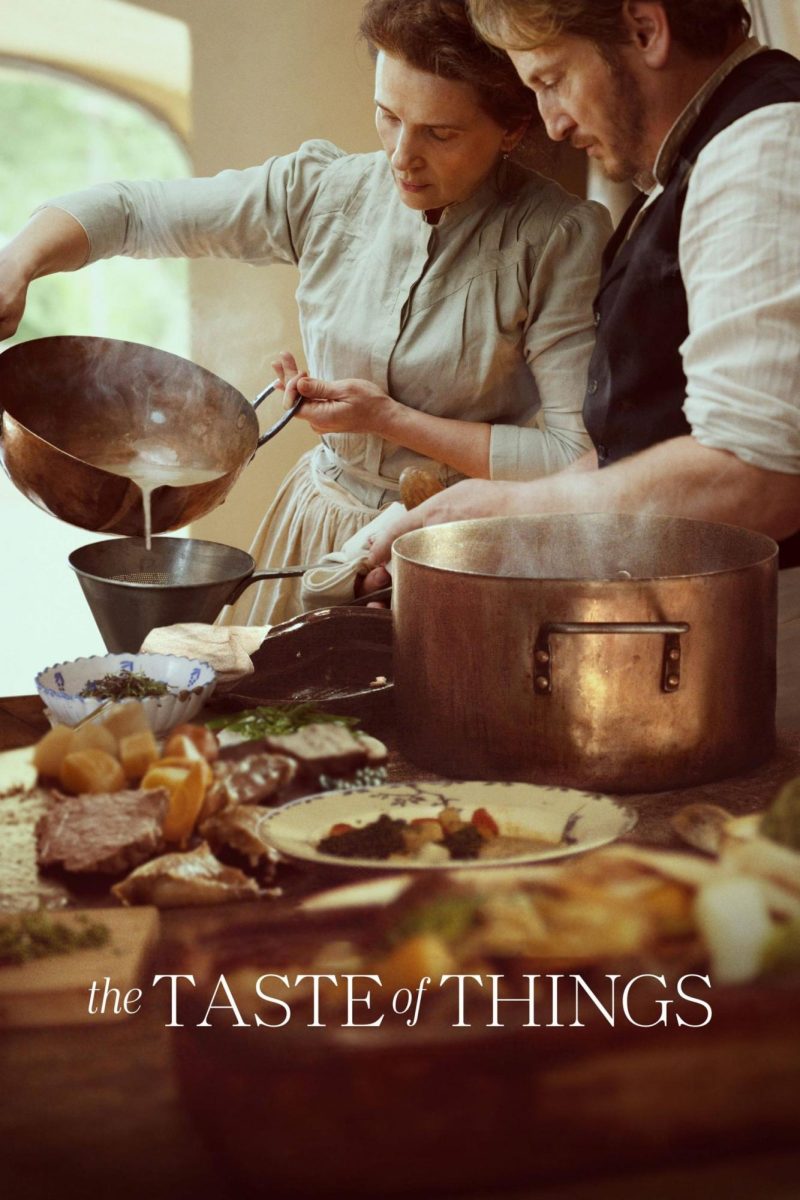

When’s the last time something you ate made you cry? This idea comes up in Taste of Things, a French romantic drama taking place in the late 19th century, and I would presume that this question would feel foreign to most Americans. It begins with a 38-minute opening sequence that serves up mouth-watering dishes and introduces the characters and dynamics between them with minimal dialogue. Eugénie, played by Juliette Binoche, works skillfully as the head cook, and directs her young assistant Violette and Pauline, Violette’s niece, with authority and grace. Dodin, played by Benoît Magimel, is identified as the owner of the country estate located in France as he bounces between helping in the kitchen and entertaining his guests. An unspoken, magnetic attraction exists between Eugénie and Dodin as they cook alongside each other. The culmination of this scene is when the meal is presented to Dodin’s guests through a number of courses, and they enjoy each one as if it were their last.

France holds a reverence for chefs because there is a higher standard and a deeper appreciation for meals. Dodin’s friends go to the kitchen to insist that Eugénie join them more often after proclaiming that she is an artist. Being a “culinary artist” in Paris takes years of experience as cooking is seen as a craft that takes time and one’s palette must develop to taste nuance. The term culinary artist is used sparingly in the West as it’s reserved for Michelin star restaurants. The standard for most restaurants has become fast service and large portions, which leaves no incentive for chefs to take their time to chase the same kind of quality and perfection. Dodin and Eugénie believe Pauline to be a culinary prodigy as she can identify the many ingredients in a multilayered broth by taste and picks up cooking techniques quickly. Later in the film, Dodin has her try bone marrow, which she dislikes, and encourages her that taste buds mature as one ages. This sentiment applies to the slow-burn love story at the center of the film that also reflects the values of aging and maturity as opposed to hookup culture and other formulations of relationships that prize instant gratification above all else.

With the cinematography that captures long scenes of the cooking process from multiple angles and the acting skills of the two leads, it is easy for the viewer to immerse themselves into Eugénie and Dodin’s world. As delicious as the loins of veal and homemade pastries appeared, I became more enamored with what the driving force was behind Eugénie and Dodin’s passion and commitment to transform each meal into a labor of love. Dodin sits down with Eugenie and their two young assistants to enjoy a simple, empty and fluffy omelet and he makes sure to tell Pauline to eat it slowly with a spoon. This is an attractive philosophy especially to someone who grew up living in the West where an omelet would be instead stuffed with a pound of vegetables, ham, and melted cheese, and devoured in seconds. Beyond that, there is a sense of depth between Dodin and Eugénie created and fostered on screen with the use of poetic dialogue, meaningful glances, and hidden complexities within their relationship that are revealed as the film progresses.

Dodin has proposed multiple times and Eugénie has denied him, saying that she likes their arrangement and doesn’t want to ruin that with change. This arrangement refers to the specific rhythms laid out by Eugénie where she will either unlock or lock the door of her room, which is an indicator for whether she wants Dodin to come inside her room. Eugénie sets the boundaries to this relationship and Dodin relentlessly wants to close the distance. Tran Ahn Hung interviewed with “the Film Experience,” and described how Eugénie clearly defines their relationship based on the women she desires to be and that Dodin comes to understand and accept this. He goes on to say that “the whole movie is about the idea of her being a free woman, and about Dodin, who accepted it.” I agree with Hung that the distance that Eugénie creates between them does add to their beautiful relationship on screen because it highlights the complex nature of relationships that is lost when characters are either oversimplified or exaggerated.

There is a palpable sense of longing created by this element of restraint that is created by Eugénie’s boundaries. This is highly countercultural to people living in the United States which has become increasingly sexualized and less romantic as a result. A great symbol for this is found midway through the film when Dodin is invited to dine at the prince of Eurasia’s house for dinner. The chefs there attempted to impress him and his friends with extravagant courses that placed value on indulgence and expensive ingredients instead of the elegance and subtlety that he holds to such high esteem. People often wrongly define freedom as doing whatever you want yet don’t account for how anything done to excess often decreases satisfaction.

Eugénie is independent and wants to make sure that Dodin understands that she wants to be her own person. She doesn’t want to be just considered as his wife, which would be common for the time period, especially when marrying someone of his status. She instead wants recognition for the food she creates and who she is as an individual. Dodin quotes Augustine, saying, “happiness is continuing to desire what we already have,” and asks her “have I ever had you?” Eugénie wrestles with the idea of marriage because she doesn’t want to be had. At the same time, I believe her independence shouldn’t be blankly praised but seen in all its complexities. She fears not being in control. In the kitchen she masterfully weaves together dishes, yet life doesn’t give us a recipe to follow. She is shown denying fainting spells throughout the film that proves this point that she doesn’t want to be seen as weak or accept the fact that she is aging and in the autumn season of her life. It is unhelpful to label these parts of her as either bad or brave. Instead, it’s important to see that each person is full of fears and personality traits and that they are given the chance to confront and integrate in a healthy way through relationships.

Eugénie’s restraint creates longing, but its main utility may be the way it opened Dodin’s eyes to see her as a real woman, as opposed to a fantasy. Longing is often associated with something unattainable as people project their ideals onto reality instead of accepting it as it is. In the same way, Eugénie’s desire for independence creates a cavern that she will eventually have to cross to accept help. A pivotal scene later in the film shows how Dodin takes the time to serve Eugénie, symbolizing that he helped her get to a place where she can be the one being served.

Whether it’s crying over delicious food that one hasn’t tried before, like Pauline does when tasting French dishes for the first time or feeling a flood of positive emotions when falling in love with someone, I don’t think anyone would disagree that these are genuinely happy moments that we should be grateful for. What Augustine’s quote leaves out is that happiness may not be what any of us are really searching for, rather we seek out relationships with people to lead us to where we haven’t yet been. Just like Dodin and Eugénie’s connection, the meaning found in life and love that we seek takes seasons to develop and the maturity to relinquish control.