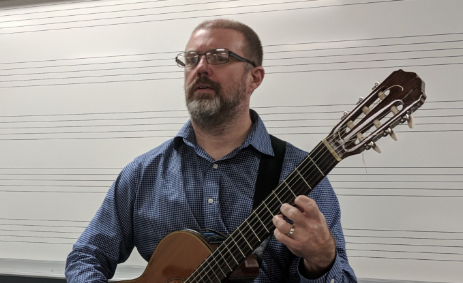

Hello, thank you so much for being willing to do this interview today.

In your own words, what makes a perfect film? And do you see a correlation in the films that you like?

I think a perfect film is one that tells a compelling story, or presents an intriguing character study, and does so in a way that fully utilizes the medium of film. It’s not simply a still camera recording the equivalent a play on a stage, but an experience that conveys its message in ways only film can do.

I understand you have your BA and MA in Film and Contemporary American Literature Studies. What was it specifically that propelled your interest in pursuing an education in film and how did your relationship with film shift/change throughout that time?

I was compelled to study film from my first film appreciation course at Minnesota State University—Mankato. Students sat in the dark in a theater-like auditorium and watched that week’s film first (on reel-to-reel film, with the professor having to change reels by hand when each ran out), took a brief break, and then returned to examine the elements of the film and discuss it in depth.

After that, I took many film courses, which were always offered by the English Departments at both Mankato and the University of Florida, which I later attended.

My most influential professor, Gregory Ulmer at the University of Florida, showed us lots of experimental, arthouse films, and also encouraged me to go into teaching. He directed my Master’s thesis, told me to be a subversive force in academia, and cheered me on through my writings and studies.

My relationship with film has grown deeply appreciative over time, as I really notice and applaud directors who can amaze, surprise, engage, and touch me anew, no matter how many movies I’ve seen.

Throughout your film career, have you observed differences in how generations engage with films and what changes have you seen in their perspectives from the beginning to the end of their classes with you?

Students in the past were more open-minded about watching things that might upset or disturb them. Gen Z students, as a whole, are more defensive and fear-based: they are constantly alert for things that are dangerous, or offensive, or triggering, and they are quick to reject them wholesale, and complain about them. This often stops them from appreciating them, in an artistic sense, and examining them to see what value or message they may contain or convey to viewers.

It’s most rewarding when students say, for example, that while they would never have chosen class films on their own, they both loved and appreciate them, and even that they are now sharing them with others, be it family, friends, or significant others.

In your own estimation, why do people watch movies?

Primarily people watch movies for entertainment. They want to escape for a few hours or be distracted from day-to-day life.

A much smaller percentage of viewers watch for both entertainment value and film artistry.

What would be some advice you would give to someone looking to derive more meaning out of the films they watch and have a more intimate experience?

Engaging in conversations with fellow viewers is one way to expand and deepen one’s experience.

Aiming to get fellow viewers to do more than express a Thumbs Up or Thumbs Down view of the movie is key; in fact, it’s best to purposefully postpone any talk of whether or not one liked a film until after things like acting, costuming, lighting, editing, plotting, etc., have been explored. This is because once people give their “Loved It!” or “Hated It!” viewpoints, they often consider the discussion over, and their opinion cemented.

However, if one is able to hold off on that initial, knee-jerk reaction (whether talking with others or simply contemplating a film on one’s own), and keep an open mind to others’ observations and thoughts (or taking the time to explore other ways of thinking about components of the film on their own), and carefully listen to and consider them, it can refine—or even shift—one’s initial stance, and give one a more holistic view and appreciation of the work.

How has being a film professor for so many years impacted the way you view films in your personal time? What genres have interested

Often when I watch films, I am considering whether it would be a good choice to analyze in a class, be it film studies or composition or literature.

Happily, this does not impact my enjoyment of film; as with reading, and examining a novel deeply, engaging in ANY text—be it a film, play, or book—makes it MORE interesting, MORE enjoyable, MORE affecting and immersive.

Did you ever watch a movie where you saw yourself with the main character? What made you connect with them?

In every film that I watch, I definitely identify with the protagonist as he or she moves through their lives.

In The Wizard of Oz, viewers are Dorothy, be they, themselves, a child or an adult; male, female, or non-binary: we ARE Dorothy; we feel for her and root for her and wonder how we’d react to and behave in similar situations.

Whenever anyone doubts or challenges the notion that they become the protagonist as they watch films (the most frequent protestation I hear is, “I can’t identify with him; he’s vile, or evil, or a “bad guy,” or “nothing like me”), I use the example of Norman Bates in Psycho, someone who is morally reprehensible, someone most people would initially claim that they could never identify with. After the murder of Marion Crane, when Norman is trying to sink her car, with her body in the trunk, in the swamp on his property, the car sinks steadily . . . until it stops, and goes no further, its top half still sticking up obviously. At that moment, the viewer feels panic and anxiety, over the fact that the car is still exposed, and the police will undoubtedly see it. Like Norman, the viewers desperately want the car to fully submerge. That is the “a-ha! moment,” the one that reveals that we, as viewers, ARE Norma Bates, experiencing his emotions, hoping he’ll succeed and be safe, wanting him to avoid capture, at least for the duration of the film.

Whether it’s a movie or a novel, that is the appeal of engaging in such texts: viewers or readers can abandon their own selves, and become someone else—live a different life, see what other realities are like—for a few magical, transcendent hours. Fiction is the only way that good people get to do this, and retain their ethics and morals and safety in their day-to-day reality.

Do you think films can change people’s lives and if so, how?

Yes. All art—film included—can be deeply affecting.

For instance, films can be inspirational, either in terms of their artistic merit, or in terms of their message. Viewers often leave a theater where they saw the main character connecting or re-connecting with a sibling, or protecting them, loving them, caring for them, thinking, “Oh, wow, I haven’t really appreciated my brother; I’m going to give him a huge hug and tell him that I love him” (or spend more time with him; or help him clean up his yard; or something else).

Art does move people in myriad ways. It’s probably difficult to pinpoint where that influence begins and ends, but we’ve all felt it, and it’s definitely real.

Whether these changes or feelings or thoughts are enduring or not is another question, but either way, this reminds me of one of my favorite quotes: “Art should comfort the disturbed, and disturb the comfortable.” –Cesar Cruz.

Thank you so much for sharing the experience and wisdom you’ve acquired.